This essay briefly discusses The Handmaid’s Tale (Margaret Atwood; 1985); The Children of Men (P.D. James; 1992); Oryx and Crake (Atwood; 2003) and The Year of the Flood (Atwood; 2009); The Gate to Women’s Country (Sheri S. Tepper; 1988); Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang (Kate Wilhelm; 1976); Always Coming Home (Ursula K. Le Guin; 1985). There are no spoilers beyond very brief summaries.

I have noticed that two sub-genres frequently get confused: the dystopian story and the post-apocalyptic story. While these two areas of future storytelling may overlap, they don’t mean the same thing at all. So let’s define some terms, shall we?

We’ll begin with apocalypse. An apocalyptic story is one that depicts the end of modern human civilization as we know it, usually due to some cataclysmic event. A nuclear war, a meteor impacting the Earth, a zombie uprising, a 99-percent fatal epidemic — all of these things can usher in the apocalypse. A post-apocalyptic story concerns itself with what happens after that apocalyptic event, whether immediately following it or far, far in the future.

Often what happens is the rise of new societies. These societies may sometimes be dystopias. A dystopia is the opposite of a utopian society. Utopias are pretty much perfect, providing for the needs of all of their citizens. Dystopias, on the other hand, are usually oppressive, totalitarian, and violent.

Utopian and dystopian societies do not have to arise out of an apocalyptic event, however. 1984 and Brave New World are both classics of the dystopian sub-genre that do not contain an apocalypse. Or take, for example, The Handmaid’s Tale, which is often mis-classified as post-apocalyptic. In that novel, a fundamentalist Christian group overthrows the current government and establishes a totalitarian society that enslaves women. Although environmental degradation has caused widespread infertility, no true apocalypse takes place. In fact, the primary point of view of the novel is of a future society looking back on this time in history.

Compare that with The Children of Men (or the movie based on it). In that case, although the apocalypse has not yet occurred, it is anticipated, because every person has lost the ability to reproduce and no children have been born in a generation. The novel could even be classified as pre-apocalyptic in that sense. This situation has directly created a dystopian government, which took power to enforce order on the growing chaos and anarchy occurring ahead of the apocalypse. So The Children of Men is an apocalyptic novel, whereas The Handmaid’s Tale is not, even though the subject matter is similar.

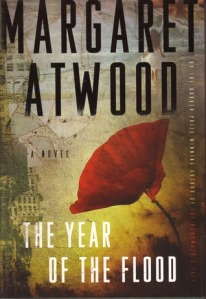

Sometimes the dystopian society is the cause of the apocalyptic event. This is the case in Atwood’s companion novels Oryx and Crake and The Year of the Flood. The futuristic society she depicts is overwhelmingly consumerist, with a huge gap between rich and poor. One character takes it upon himself to engineer a virus to wipe out humankind and start all over again from scratch.

While I enjoy dystopian novels of all kinds, I am most interested in those dystopias that directly arise from an apocalyptic event. There are numerous examples of these, which may be why the two terms are so often confused. The Gate to Women’s Country is a dystopia masquerading as utopia, a common trope. After a devastating war, a society of walled cities based on ancient Greece arose. The cities are governed by women, while the men are forced to live outside the city walls as soldiers. Another good example is Where Late the Sweet Birds Sang, where the human survivors rely on cloning to reproduce. The cloned generations gradually change, losing their individuality and other essential human qualities, and oppressing anyone who differs from the norm.

If it’s a true post-apocalyptic utopia you’re looking for, you might try Always Coming Home. Set in the far future California, it depicts an agrarian, idyllic society. Although they have access to technology — computer networks that survived the pre-apocalyptic civilization record their stories and occasionally provide information — they maintain an pre-Industrial Age way of life. Such an idealized lifestyle certainly seems unattainable without an apocalypse to first wipe the slate clean and allow us to start all over — and do it right this time.