Here is my original review of Who Fears Death (Nnedi Okorafor; 2010). This review includes spoilers for both Who Fears Death and its prequel, The Book of Phoenix (Okorafor; 2015).

As a prequel to Who Fears Death, it is impossible not to compare these two books. I think that Who Fears Death was much more successful than The Book of Phoenix on several levels. The Book of Phoenix tells the story of the apocalyptic event that created the far future world of Who Fears Death, instigated by a genetically engineered immortal weapon named Phoenix.

As a prequel to Who Fears Death, it is impossible not to compare these two books. I think that Who Fears Death was much more successful than The Book of Phoenix on several levels. The Book of Phoenix tells the story of the apocalyptic event that created the far future world of Who Fears Death, instigated by a genetically engineered immortal weapon named Phoenix.

Who Fears Death sits clearly in the realm of fantasy/magical realism. This genre choice works well for the style of story, which incorporates African myth and folklore. The Book of Phoenix is more a science fiction story–or to be accurate, it employs the tropes of superhero comics with a nod to SF. Yet the style is deliberately that of oral storytelling, presumably drawn from African traditions (given the themes), with a tendency toward repetition, circling around events, and some unnecessary tangents. I didn’t think these two choices meshed at all well together. I had several unanswered questions regarding the more science fictional aspects of the plot that probably wouldn’t have bothered me as much in a more fantastic setting.

Both stories center around a female character with incredible powers who is also incredibly angry. Who Fears Death did not feel the need to justify or soften its heroine’s anger, who is reacting to the sexist and racist oppression she experiences. The Book of Phoenix focuses on racial oppression, particularly the exploitation of African peoples by the West, and this theme is very powerful. Unlike Who Fears Death, though, it has no corresponding feminist message. Toward the end, as Phoenix is wreaking her vengeance, there is a very disturbing paragraph, where Phoenix notes that as a woman, she is unable to control her anger or channel it properly. If she were a man, she would have been a better superhero, she seems to say. This observation comes out of nowhere and is difficult to explain. Are we supposed to believe that this is simply Phoenix’s naivete talking? If so, it’s clumsily handled and, I think, stands in opposition to the theme I enjoyed most in Who Fears Death, which was the power and rightness of women’s anger.

I am not very familiar with African myths beyond the basics of Yoruba, so I can’t really comment on these themes in either books, although I am certain that Okorafor has knowledgeably incorporated myth into both. However, it’s hard to miss the biblical references. If Who Fears Death can be seen as an upending of the Christ story, with an angry and vengeful Christ figure at its center, then The Book of Phoenix is clearly Old Testament, with all its falls: the fall of the tower, the fall of angels, the fall of man, culminating in a waterless flood, the scorching of the Earth with fire. Is Phoenix then a Lucifer figure, or is this another upending? She sees herself as a villain, not a heroine, and she seems to root her villainy in her femaleness (Eve in the garden). Are we supposed to condemn her then? Given the sheer evil of the forces she was up against, I don’t want to condemn her. I just don’t feel like Okorafor gives us enough to really understand what she is trying to say with this book. It’s frustrating.

That’s how I mainly felt upon finishing: frustrated. I was looking forward to having some of the unanswered questions in Who Fears Death answered. I don’t feel they really were. I still don’t understand how Phoenix’s story–which becomes the basis of the Great Book, or the religious text that everyone abides by in Who Fears Death–is twisted to justify the oppression and enslavement of black Africans by Arabic Africans. I didn’t feel a true continuity between these two stories. I think I would have been better off letting Who Fears Death stand alone.

Winter Well, edited by Kay T. Holt (2013), is a collection of four novellas that certainly run the gamut of genres that might be categorized as “speculative fiction.” The first, “To the Edges” by M. Fenn, is set in an apocalyptic near future United States undergoing social collapse. Next is “Copper” by Minerva Zimmerman, a futuristic tech noir detective story. “This Other World” by Anna Caro is more straightforward social science fiction, set on an alien planet. The final offering, “The Second Wife” by Marissa James, is straight-up fantasy.

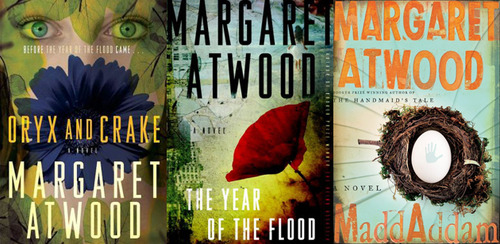

Winter Well, edited by Kay T. Holt (2013), is a collection of four novellas that certainly run the gamut of genres that might be categorized as “speculative fiction.” The first, “To the Edges” by M. Fenn, is set in an apocalyptic near future United States undergoing social collapse. Next is “Copper” by Minerva Zimmerman, a futuristic tech noir detective story. “This Other World” by Anna Caro is more straightforward social science fiction, set on an alien planet. The final offering, “The Second Wife” by Marissa James, is straight-up fantasy. Consider, for instance, Atwood’s most well-known book, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), which was nominated for the Booker Prize but won the Arthur C. Clarke Award the very first time it was given out. It is set in a dystopian future, in which the U.S. government has been taken over by Christian fundamentalists and a lot of basic rights have been stripped away. Due to extreme pollution, many people have become infertile. Those women who are fertile are enslaved as Biblical-style handmaids, conceiving and bearing children for wealthy, infertile women. Its dystopian, futuristic setting place it squarely in the science fiction tradition.

Consider, for instance, Atwood’s most well-known book, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), which was nominated for the Booker Prize but won the Arthur C. Clarke Award the very first time it was given out. It is set in a dystopian future, in which the U.S. government has been taken over by Christian fundamentalists and a lot of basic rights have been stripped away. Due to extreme pollution, many people have become infertile. Those women who are fertile are enslaved as Biblical-style handmaids, conceiving and bearing children for wealthy, infertile women. Its dystopian, futuristic setting place it squarely in the science fiction tradition. The Blind Assassin (2000), which won the Booker Prize, is not as straightforward in terms of genre, but it does contain science fiction elements. Its structure is very unusual, in that it is a novel within a novel within a novel. The framing structure is a straightforward historical novel about a wealthy Canadian family’s fall from grace during the Depression and World War II. Within this novel is an intertwined story of two unnamed lovers and their clandestine affair. During their meetings, the lovers — one of whom is a pulp writer — tell each other a bizarre fable that takes place on an alien planet, which underscores their unspoken feelings for each other. The fable, titled The Blind Assassin, is turned into a novel by one of the characters and develops a cult-like following. The intricate structure makes this an engrossing novel, but it is questionable whether it can be called science fiction. Regardless, Atwood is comfortable using tropes of the genre in exciting and unusual ways when it suits her.

The Blind Assassin (2000), which won the Booker Prize, is not as straightforward in terms of genre, but it does contain science fiction elements. Its structure is very unusual, in that it is a novel within a novel within a novel. The framing structure is a straightforward historical novel about a wealthy Canadian family’s fall from grace during the Depression and World War II. Within this novel is an intertwined story of two unnamed lovers and their clandestine affair. During their meetings, the lovers — one of whom is a pulp writer — tell each other a bizarre fable that takes place on an alien planet, which underscores their unspoken feelings for each other. The fable, titled The Blind Assassin, is turned into a novel by one of the characters and develops a cult-like following. The intricate structure makes this an engrossing novel, but it is questionable whether it can be called science fiction. Regardless, Atwood is comfortable using tropes of the genre in exciting and unusual ways when it suits her. With her more recent

With her more recent