Books discussed in this essay: Herland (Charlotte Perkins Gilman; 1915), The Female Man (Joanna Russ; 1975), The Gates to Women’s Country (Sheri S. Tepper; 1988), Woman on the Edge of Time (Marge Piercy; 1976), and Always Coming Home (Ursula K. Le Guin; 1985). Some spoilers.

What does a world look like where women are equal to men?

Women writers have tried to imagine such a utopia. Perhaps not surprisingly, for many of them it was a world without men at all.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland may be the earliest example of a feminist utopia. In Herland, three male explorers discover an isolated country in the South American jungle populated only by women. It is a perfect place, where women live in harmony with one another, spontaneously reproduce, and have advanced their society due to lack of conflict. The only fly in the ointment is their male visitors, who can’t help their innate sexism, but these confident women mostly just laugh them off. At first blush, Herland seems fairly ideal.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s Herland may be the earliest example of a feminist utopia. In Herland, three male explorers discover an isolated country in the South American jungle populated only by women. It is a perfect place, where women live in harmony with one another, spontaneously reproduce, and have advanced their society due to lack of conflict. The only fly in the ointment is their male visitors, who can’t help their innate sexism, but these confident women mostly just laugh them off. At first blush, Herland seems fairly ideal.

But there are problems with the all-female utopia that Gilman fails to address. For instance, the women all seem asexual, which ignores a fundamental aspect of our nature in favor of combatting the sexual objectification of women. Also, it is difficult to imagine any group of human beings living together without conflict, no matter what their gender. Still, I’d recommend Herland, a quick read, just for its historical value as an early work of feminism, even if does avoid some of the more difficult questions that are raised.

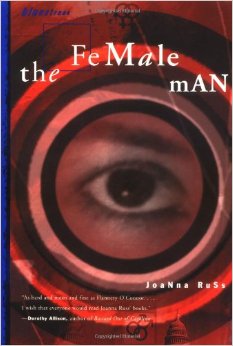

In 1975, Joanna Russ imagined a similar utopia in The Female Man, this time an alternate world called Whileaway. However, her utopia is not so perfect. Reproduction is handled more realistically, and the women do fight among themselves, often violently. This is one of four alternate worlds Russ presents in the novel. Another, most definitely not a utopia, depicts men and women living separately in a perpetual state of war. Just as in Herland, The Female Man cannot imagine a world where men and women can live together in equality and harmony.

In 1975, Joanna Russ imagined a similar utopia in The Female Man, this time an alternate world called Whileaway. However, her utopia is not so perfect. Reproduction is handled more realistically, and the women do fight among themselves, often violently. This is one of four alternate worlds Russ presents in the novel. Another, most definitely not a utopia, depicts men and women living separately in a perpetual state of war. Just as in Herland, The Female Man cannot imagine a world where men and women can live together in equality and harmony.

While I admit that I too have spent a happy hour or so imagining a world without men, it’s not practical. We must envision ways women can achieve equality while still keeping men around, if only for the very basic reason that we are one species who are all in this together–or at least, we should be. Also, many women happen to enjoy the company of men.

Sheri S. Tepper moderates this vision of a feminist utopia somewhat in The Gates to Women’s Country. In her post-apocalyptic far future, women and men mostly live separately, the women inside a beautiful walled city that hearkens back to the civilization of the ancient Greeks, the men outside the walls in barracks, constantly training for war. Only a few men are allowed inside to serve the women, carefully selected for their submissive traits.

Sheri S. Tepper moderates this vision of a feminist utopia somewhat in The Gates to Women’s Country. In her post-apocalyptic far future, women and men mostly live separately, the women inside a beautiful walled city that hearkens back to the civilization of the ancient Greeks, the men outside the walls in barracks, constantly training for war. Only a few men are allowed inside to serve the women, carefully selected for their submissive traits.

As in the previous two novels, Tepper’s world is one in which men and women cannot live together naturally, due to the innate characteristics of men. The soldiers are basically overgrown children who perceive women as helpless objects requiring protection and impregnation with sons. The servitors are the flip side of the coin: wise, calm, strong, always in control of themselves—the “perfect men” in this women’s fantasy. However, they are not perfect by nature, but by design, and therefore they are not real.

A utopian vision where men and women do co-exist can be found in Woman on the Edge of Time by Marge Piercy. A present-day woman time-travels to the future and is shown what an egalitarian society might be like. Although men and women live together in this utopia, there is virtually no distinction between them. The time traveler sometimes cannot even tell what gender her guide is. The language has changed, as well, so that gender pronouns are no longer used. While at first glance this seems like a desirable way of achieving a perfect communal society, erasing the differences between us again defies human nature. Although our differences often inspire oppression, they are also what make us interesting, and quite possibly what enable us to innovate and adapt so well.

A utopian vision where men and women do co-exist can be found in Woman on the Edge of Time by Marge Piercy. A present-day woman time-travels to the future and is shown what an egalitarian society might be like. Although men and women live together in this utopia, there is virtually no distinction between them. The time traveler sometimes cannot even tell what gender her guide is. The language has changed, as well, so that gender pronouns are no longer used. While at first glance this seems like a desirable way of achieving a perfect communal society, erasing the differences between us again defies human nature. Although our differences often inspire oppression, they are also what make us interesting, and quite possibly what enable us to innovate and adapt so well.

The utopia presented in Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home imagines a future of communal living where gender differences have been preserved. This utopia is similar to the one in Woman on the Edge of Time: people live cooperatively in villages, eschewing technology and the trappings of our present-day consumerist society, pursuing their passions and strengths, moving fluidly between relationships, and governing and raising children as a group. Yet even Le Guin has a hard time envisioning such a utopia without rejecting almost all the achievements of the modern day. To be our better selves, we have to return to a more primitive version of ourselves. There is a certain attraction to this simpler life, but is it realistic? Once knowledge has been gained, once technologies have been developed, we don’t let that go. We have to build on what came before, not tear it down.

I have yet to read a utopian vision that posits equality for all and yet society continues to progress along a forward trajectory (the only thing that seems to come close may be the Star Trek universe). I would like to. For forward-thinking writers, though, it is easier–and certainly more interesting–to imagine the dystopias that might be. But that is the subject of another essay.

Four women from alternate universes come together in this work of feminist speculative fiction.

Four women from alternate universes come together in this work of feminist speculative fiction.