Margaret Atwood says “now is not the time for realistic fiction,” but is her writing science fiction? She would deny it, preferring the more nebulous term, “speculative fiction.” Regardless, in many of her novels, even her more mainstream ones, she deals with what-if’s and what-might-be’s, rather than what is.

On the subject, Atwood says:

“I like to make a distinction between science fiction proper and speculative fiction. For me, the science fiction label belongs on books with things in them that we can’t yet do, such as going through a wormhole in space to another universe; and speculative fiction means a work that employs the means already to hand, such as DNA identification and credit cards, and that takes place on Planet Earth. But the terms are fluid.”

Atwood is generally considered a literary writer by critics who wouldn’t dream of dipping into the genre ghetto, but she gets away with writing fiction that could easily be called science fiction. And she wins major awards for it! She doesn’t write only science fiction, though, but also tries her hand at other genres, such as historical fiction. Not many writers can be successful at genre-hopping, but more are trying it. Michael Chabon and Kazuo Ishiguro spring to mind.

Consider, for instance, Atwood’s most well-known book, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), which was nominated for the Booker Prize but won the Arthur C. Clarke Award the very first time it was given out. It is set in a dystopian future, in which the U.S. government has been taken over by Christian fundamentalists and a lot of basic rights have been stripped away. Due to extreme pollution, many people have become infertile. Those women who are fertile are enslaved as Biblical-style handmaids, conceiving and bearing children for wealthy, infertile women. Its dystopian, futuristic setting place it squarely in the science fiction tradition.

Consider, for instance, Atwood’s most well-known book, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), which was nominated for the Booker Prize but won the Arthur C. Clarke Award the very first time it was given out. It is set in a dystopian future, in which the U.S. government has been taken over by Christian fundamentalists and a lot of basic rights have been stripped away. Due to extreme pollution, many people have become infertile. Those women who are fertile are enslaved as Biblical-style handmaids, conceiving and bearing children for wealthy, infertile women. Its dystopian, futuristic setting place it squarely in the science fiction tradition.

I think The Handmaid’s Tale was so successful and has been so widely read because its core message is a frightening warning about how quickly and easily the freedoms we take for granted can be stripped away. What struck me the last time I read it is the method of depriving women of their rights that was used: Their bank accounts were frozen, and electronic access to money was cut off. As we are well on our way to a cashless society, this struck me as an all-too-real danger, one we placidly accept.

The Blind Assassin (2000), which won the Booker Prize, is not as straightforward in terms of genre, but it does contain science fiction elements. Its structure is very unusual, in that it is a novel within a novel within a novel. The framing structure is a straightforward historical novel about a wealthy Canadian family’s fall from grace during the Depression and World War II. Within this novel is an intertwined story of two unnamed lovers and their clandestine affair. During their meetings, the lovers — one of whom is a pulp writer — tell each other a bizarre fable that takes place on an alien planet, which underscores their unspoken feelings for each other. The fable, titled The Blind Assassin, is turned into a novel by one of the characters and develops a cult-like following. The intricate structure makes this an engrossing novel, but it is questionable whether it can be called science fiction. Regardless, Atwood is comfortable using tropes of the genre in exciting and unusual ways when it suits her.

The Blind Assassin (2000), which won the Booker Prize, is not as straightforward in terms of genre, but it does contain science fiction elements. Its structure is very unusual, in that it is a novel within a novel within a novel. The framing structure is a straightforward historical novel about a wealthy Canadian family’s fall from grace during the Depression and World War II. Within this novel is an intertwined story of two unnamed lovers and their clandestine affair. During their meetings, the lovers — one of whom is a pulp writer — tell each other a bizarre fable that takes place on an alien planet, which underscores their unspoken feelings for each other. The fable, titled The Blind Assassin, is turned into a novel by one of the characters and develops a cult-like following. The intricate structure makes this an engrossing novel, but it is questionable whether it can be called science fiction. Regardless, Atwood is comfortable using tropes of the genre in exciting and unusual ways when it suits her.

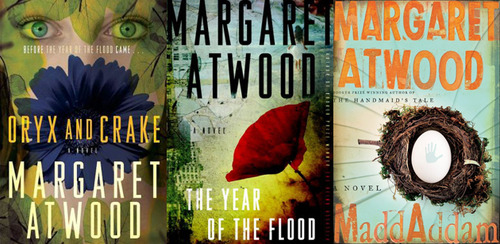

With her more recent MaddAddam trilogy, Atwood has a harder time making the case that she is not in fact writing science fiction. The dystopian future she imagines relies on the products of genetic engineering. A genuine mad scientist applies his eugenics research to create a race of people, then releases a bio-engineered virus to bring about the apocalypse. Her most recent novel, The Heart Goes Last, is another dystopia that was originally published in installments on the Internet.

With her more recent MaddAddam trilogy, Atwood has a harder time making the case that she is not in fact writing science fiction. The dystopian future she imagines relies on the products of genetic engineering. A genuine mad scientist applies his eugenics research to create a race of people, then releases a bio-engineered virus to bring about the apocalypse. Her most recent novel, The Heart Goes Last, is another dystopia that was originally published in installments on the Internet.

I enjoy it when authors break the artificial boundaries of genre established by publishing companies and bookstores. Atwood’s fiction may transcend labels, but she speaks to those of us who love science fiction and its speculations on what might be.

Winter Well, edited by Kay T. Holt (2013), is a collection of four novellas that certainly run the gamut of genres that might be categorized as “speculative fiction.” The first, “To the Edges” by M. Fenn, is set in an apocalyptic near future United States undergoing social collapse. Next is “Copper” by Minerva Zimmerman, a futuristic tech noir detective story. “This Other World” by Anna Caro is more straightforward social science fiction, set on an alien planet. The final offering, “The Second Wife” by Marissa James, is straight-up fantasy.

Winter Well, edited by Kay T. Holt (2013), is a collection of four novellas that certainly run the gamut of genres that might be categorized as “speculative fiction.” The first, “To the Edges” by M. Fenn, is set in an apocalyptic near future United States undergoing social collapse. Next is “Copper” by Minerva Zimmerman, a futuristic tech noir detective story. “This Other World” by Anna Caro is more straightforward social science fiction, set on an alien planet. The final offering, “The Second Wife” by Marissa James, is straight-up fantasy. Consider, for instance, Atwood’s most well-known book, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), which was nominated for the Booker Prize but won the Arthur C. Clarke Award the very first time it was given out. It is set in a dystopian future, in which the U.S. government has been taken over by Christian fundamentalists and a lot of basic rights have been stripped away. Due to extreme pollution, many people have become infertile. Those women who are fertile are enslaved as Biblical-style handmaids, conceiving and bearing children for wealthy, infertile women. Its dystopian, futuristic setting place it squarely in the science fiction tradition.

Consider, for instance, Atwood’s most well-known book, The Handmaid’s Tale (1985), which was nominated for the Booker Prize but won the Arthur C. Clarke Award the very first time it was given out. It is set in a dystopian future, in which the U.S. government has been taken over by Christian fundamentalists and a lot of basic rights have been stripped away. Due to extreme pollution, many people have become infertile. Those women who are fertile are enslaved as Biblical-style handmaids, conceiving and bearing children for wealthy, infertile women. Its dystopian, futuristic setting place it squarely in the science fiction tradition. The Blind Assassin (2000), which won the Booker Prize, is not as straightforward in terms of genre, but it does contain science fiction elements. Its structure is very unusual, in that it is a novel within a novel within a novel. The framing structure is a straightforward historical novel about a wealthy Canadian family’s fall from grace during the Depression and World War II. Within this novel is an intertwined story of two unnamed lovers and their clandestine affair. During their meetings, the lovers — one of whom is a pulp writer — tell each other a bizarre fable that takes place on an alien planet, which underscores their unspoken feelings for each other. The fable, titled The Blind Assassin, is turned into a novel by one of the characters and develops a cult-like following. The intricate structure makes this an engrossing novel, but it is questionable whether it can be called science fiction. Regardless, Atwood is comfortable using tropes of the genre in exciting and unusual ways when it suits her.

The Blind Assassin (2000), which won the Booker Prize, is not as straightforward in terms of genre, but it does contain science fiction elements. Its structure is very unusual, in that it is a novel within a novel within a novel. The framing structure is a straightforward historical novel about a wealthy Canadian family’s fall from grace during the Depression and World War II. Within this novel is an intertwined story of two unnamed lovers and their clandestine affair. During their meetings, the lovers — one of whom is a pulp writer — tell each other a bizarre fable that takes place on an alien planet, which underscores their unspoken feelings for each other. The fable, titled The Blind Assassin, is turned into a novel by one of the characters and develops a cult-like following. The intricate structure makes this an engrossing novel, but it is questionable whether it can be called science fiction. Regardless, Atwood is comfortable using tropes of the genre in exciting and unusual ways when it suits her. With her more recent

With her more recent