These are my first impressions after reading Boneshaker (Cherie Priest; 2009) in January 2010. Slight spoilers.

Boneshaker is a steampunk novel set in an alternate Seattle in the 1880s. Steampunk is a sub-genre of science fiction set in an era where steam power is widely used. Science fiction elements include technological inventions that never actually existed or that were invented early (such as steam-powered computers), as well as alternate-history speculations that would allow such innovations to happen. In Boneshaker, Priest has also thrown zombies into the mix, but with a scientific, rather than a supernatural, cause. To add to the effect, the book is printed in brown ink, giving it an antiquated look that is surprisingly easy on the reader’s eyes.

Boneshaker is a steampunk novel set in an alternate Seattle in the 1880s. Steampunk is a sub-genre of science fiction set in an era where steam power is widely used. Science fiction elements include technological inventions that never actually existed or that were invented early (such as steam-powered computers), as well as alternate-history speculations that would allow such innovations to happen. In Boneshaker, Priest has also thrown zombies into the mix, but with a scientific, rather than a supernatural, cause. To add to the effect, the book is printed in brown ink, giving it an antiquated look that is surprisingly easy on the reader’s eyes.

Before the story begins, an excerpt from a book called Unlikely Episodes in Western History sets the stage. The setting is a slightly altered America, where the Civil War stretched on and on, and the Gold Rush boomed early, turning Seattle into a bustling mining town by 1879. With the Gold Rush moving farther north, the Russians held a competition to develop a machine that could mine gold from underneath ice. Leviticus Blue, a Seattle inventor, came up with a monstrous machine called the Boneshaker, but when he started it up, something went wrong and it tore a destructive tunnel underneath downtown. This released a trapped gas, later christened the Blight, that turned those who breathed it into “rotters” — zombies, effectively. Seattle had to be evacuated and a massive wall erected around downtown, keeping in both the Blight and the rotters.

Fifteen years later, Blue’s widow, Briar Wilkes, is eking out a living on Seattle’s Outskirts. She discovers that her teenage son, Zeke, has sneaked inside the Wall to find evidence that might exonerate his father. After an earthquake destroys Zeke’s one way out, Briar sets out to rescue him. And thus begins an adventure that includes a dirigible crash, several zombie chases, and a showdown with a mad genius named Dr. Minnericht, who controls the illegal trade in a drug made from the Blight from within the city Wall.

Priest has vividly and effectively created her steampunk world of walled-off Seattle, where the air is yellow and obscured by the heavy gas, a warren of tunnels and jerry-rigged elevators crisscross the city, and huge dirigibles carrying air pirates float silently overhead. The remaining human inhabitants of the city move through this dreamlike world wearing gas masks, some of them almost post-human in their elaborate breathing apparatuses or sporting mechanized arms. Dr. Minnericht is the most striking and least human of them all, outfitted in a skull-like gas mask of pipes and valves, with glowing blue lenses for eyes, lording it over the city from an opulently furnished buried train station.

Unfortunately, the story doesn’t quite measure up to the intricate world that Priest has imagined. A straightforward adventure story, it doesn’t have much to say beyond that in terms of a larger theme or message. Still, it is a fun story that would probably make a great movie (if the actors didn’t have to cover their faces with gas masks the whole time).

Boneshaker is the first novel set in the fictional world called the Clockwork Century by Priest. Priest has previously published a trilogy of Southern Gothic horror novels.

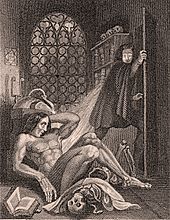

Those who take the time to read the book may be surprised to find that Frankenstein’s monster is not a green bolt-head with a limited vocabulary. Although larger and stronger than most men, he is actually intelligent and an eloquent speaker. After trying to interact with people and being rejected because of his hideous appearance, the monster realizes that no human will accept him and he is doomed to isolation. He becomes obsessed with seeking vengeance on his creator by murdering members of his family. Frankenstein vows to destroy the monster, and the two engage in a chase that finishes in the Arctic.

Those who take the time to read the book may be surprised to find that Frankenstein’s monster is not a green bolt-head with a limited vocabulary. Although larger and stronger than most men, he is actually intelligent and an eloquent speaker. After trying to interact with people and being rejected because of his hideous appearance, the monster realizes that no human will accept him and he is doomed to isolation. He becomes obsessed with seeking vengeance on his creator by murdering members of his family. Frankenstein vows to destroy the monster, and the two engage in a chase that finishes in the Arctic.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](https://i0.wp.com/img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png)