This essay also discusses Into the Forest (Jean Hegland; 1996); A Gift Upon the Shore (M.K. Wren; 1990); and Always Coming Home (Ursula K. Le Guin; 1985), among various other stalwarts of the post-apocalyptic sub-genre. There will be spoilers for these books.

Pop quiz, hotshot. It’s the apocalypse: What do you do? What. Do. You. Do?

If hundred (thousands?) of post-apocalyptic books and movies are to believed, you break out your cache of automatic weapons, gun down every guy you see, capture a woman and lock her in a cage for later, then chow down on some roasted baby.

There is a certain amount of wish fulfillment going on there. The apocalypse novel is one part fear, one part fantasy. All the rules are suddenly gone; you can do whatever you want! It’s a dim view of humanity that assumes that all people want to do is murder, rape, and eat human flesh. As if all that’s keeping us from murdering each other are electricity and laws.

This is a fantasy, though, because this is not what people do. Yes, people have done all those things; there are plenty of examples to point to. But as a general rule, people prefer to live together cooperatively. Thousands of years of human history backs me up on this. The whole of human history has been a progression away from wanton violence and brutality. In a disaster, our best natures tend to come out, more so than our worst. We help our neighbors; we don’t blow them away.

Station Eleven presents a more realistic apocalypse than these earlier views. Of course there is violence, but violence is not the raison d’etre for the book. The terrible first years are elided entirely; we prefer not to talk about that. Instead, the post-apocalyptic sections focus on men and women coming together to survive, build community, and preserve what they feel is worthwhile. Sometimes they have to kill, but only when they have to. The only character in Station Eleven who hearkens back to the cliche of the every-man-for-himself apocalypse is the Prophet, and he’s clearly a deviant.

Station Eleven presents a more realistic apocalypse than these earlier views. Of course there is violence, but violence is not the raison d’etre for the book. The terrible first years are elided entirely; we prefer not to talk about that. Instead, the post-apocalyptic sections focus on men and women coming together to survive, build community, and preserve what they feel is worthwhile. Sometimes they have to kill, but only when they have to. The only character in Station Eleven who hearkens back to the cliche of the every-man-for-himself apocalypse is the Prophet, and he’s clearly a deviant.

It’s hard to say whether this focus on community building and preservation is a feminine characteristic. Most of the violent, no-holds-barred apocalypses have been written by men and are inhabited mainly by male characters. (For some good examples, see Lucifer’s Hammer; The Postman; Swan Song; The Road). Contrast these with a few examples by women: A Gift Upon the Shore and Into the Forest. Each of these post-apocalyptic stories focuses on a pair of women and is more concerned with rebuilding–albeit on different terms–than tearing down.

There’s a catch, though: no boys allowed! When men enter these books, what do they do first? Rape, murder, subjugate their wives. This is also a kind of fantasy, a feminist fantasy. It can be hard to imagine a utopia as long as there are men around. An apocalyptic event is pretty much required if we want to create a truly egalitarian society. Always Coming Home describes such a society, rebuilt on the ashes of our world, where men don’t know they are supposed to dominate women. Indeed, the people of Always Coming Home could be the far-future descendants of Into the Forest’s Eva and Nell.

There’s a catch, though: no boys allowed! When men enter these books, what do they do first? Rape, murder, subjugate their wives. This is also a kind of fantasy, a feminist fantasy. It can be hard to imagine a utopia as long as there are men around. An apocalyptic event is pretty much required if we want to create a truly egalitarian society. Always Coming Home describes such a society, rebuilt on the ashes of our world, where men don’t know they are supposed to dominate women. Indeed, the people of Always Coming Home could be the far-future descendants of Into the Forest’s Eva and Nell.

I don’t want to live in a world where I’m likely to be raped, decapitated, and eaten while I’m out gathering my breakfast blueberries. But I don’t want to live in a world without any guys in it either, for all the obvious reasons. I like to think we are all in this together.

Station Eleven is different because it imagines what ordinary people might really do if most of the world’s population was suddenly wiped out. People are more likely to cooperate than to brutalize one another. People are more likely to live together than wander the wilderness alone. It’s a lot easier for a group of people to feed and shelter themselves. We know this already. A sudden disaster, no matter how calamitous, would not fundamentally change that. It would be literally insane to wantonly kill and rape the random people you meet who could quite possibly become your doctor, your engineer, your master gardener.

And that’s another way Station Eleven stands out: It rejects the notion that an apocalyptic event automatically leads to regression and barbarism. This is a trope so old it’s got whiskers, but yet writers keep writing it. After the apocalypse, not only will we all turn inexplicably violent, but we’ll also give up on everything we’ve created: all our scientific knowledge, our technology, our art, our progress.

Earth Abides by George R. Stewart is not as barbaric as most other apocalypses, but it’s just as pessimistic. It doesn’t take long–only a generation–for people to forget how to grow food, live in houses, read! And they like it better that way. In A Gift Upon the Shore, Mary and Rachel make it their mission to preserve books–and thus all the human knowledge–for later generations. They wrap up the books and lock them away, but they don’t use them. Into the Forest goes one step farther: burn the books. The two sisters turn their backs on technology and civilization, and return to nature. Always Coming Home is the utopian outcome of where Into the Forest begins, a far-future nature-based society that has almost completely rejected technology, with barely a memory of what came before.

Earth Abides by George R. Stewart is not as barbaric as most other apocalypses, but it’s just as pessimistic. It doesn’t take long–only a generation–for people to forget how to grow food, live in houses, read! And they like it better that way. In A Gift Upon the Shore, Mary and Rachel make it their mission to preserve books–and thus all the human knowledge–for later generations. They wrap up the books and lock them away, but they don’t use them. Into the Forest goes one step farther: burn the books. The two sisters turn their backs on technology and civilization, and return to nature. Always Coming Home is the utopian outcome of where Into the Forest begins, a far-future nature-based society that has almost completely rejected technology, with barely a memory of what came before.

Again, this makes no sense. In a survival situation, why would we give up any advantages we had? We wouldn’t bury or burn our books; we’d read them. We wouldn’t throw away our technology; we’d try to use it any way we could. Station Eleven is a more hopeful book than either Into the Forest or A Gift Upon the Shore. The survivors build their villages in truck stops and airports, which makes sense in terms of access to resources. They struggle against a return to barbarity, which comes closer to the truth of human experience, a long struggle to lift ourselves up. They preserve music and theater; they make a museum of the remnants of the technological age.

While other apocalypses revel in the dark underbelly of human nature, they forget our universal characteristics. People have always felt driven to discover what we don’t know and to create art. We yearn for a connection to our past, our ancestors, and to preserve our memories. No matter what our species has gone through, we’ve never stopped doing these things. Station Eleven not only shows post-apocalyptic survivors doing these things, but it declares that these are the only things worth doing. Survival is insufficient, after all.

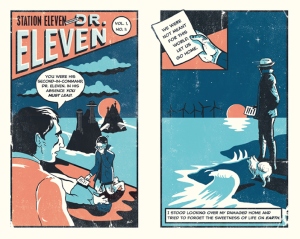

In Station Eleven, Shakespeare lives on. A traveling orchestra risks their lives to play music for others. And the loss of a comic book is a profound tragedy. Station Eleven takes place in the past as much as in the future because we live in both. If there were an apocalypse, and there were survivors, the link to the past would not break. While most post-apocalyptic books are about losing our humanity, Station Eleven is about reinforcing what makes us human.

We traveled so far and your friendship meant everything. It was very difficult, but there were moments of beauty. Everything ends. I am not afraid. — Station Eleven

For further reading (leaving the blog): My first impressions of Station Eleven; It’s the end of the world as she knows it (NewYork Times Book Review)